It was so grey as I descended into Phuket that I couldn’t tell which direction the plane was landing from. Painted in the morose light of 2022’s first Wednesday, all the island’s landmarks took on the same anonymous color and shape, as if the entire scene was a giant 3D Rorschach test.

I tried not to dwell on it. The musical taste of my friend Allano, who had come to get me from his hometown on the mainland, made this easy. Playing in the background was a strange remix of “Rocket Man” featuring Dua Lipa and an unflattering digital approximation of what was once Elton John’s voice.

Instead, it dawned on me that we were headed in the wrong direction. Sarasin Bridge – 11 km, read the sign pointing toward Phang Nga, our ultimate destination. We turned the other way.

I was in southern Thailand, of course, to see Allano and his family, so like I did for the void that existed where a big, beautiful sky had once been, I ignored any misgivings I felt.

“We had to postpone it,” Allano’s sister Irin said to me when I asked her about how her wedding, which was just months away the last time I saw her in late 2019, had gone. This might’ve seemed like a stupid question if you, too, lived through the coronavirus pandemic; it seems less stupid when you remember that Thailand barely had a wave of infection in 2020.

Irin, for her part, did not elaborate, but she did answer the implicit question bouncing around inside my head. “We’re headed to Kathu to meet Doppler now, actually,” she said, referring to her fiancé whom I still hadn’t met. “That’s why we didn’t take you directly back to Raan Jeh Nong.”

She was referring, of course, to the restaurant owned by her and Allano’s mother, a woman who is a very big deal in her village of Kalai. She self-describes as my Thai mother, a claim she made back the very first time I met her, in November 2017, a few months after I first met Allano in Bangkok.

J’Nong, as everyone calls her, was as happy as ever to see me when the three of us finally rolled into her raan aahaan about five hours after my plane landed. By this time, the monochrome sky had given way to a milky blue one puffed with clouds like whipped cream whooshed out of a can.

She was absolutely elated by the time the evening ended. No doubt because I thanked her for the delicious sukiyaki meal she had her staff prepared by making American-style cocktails with the liquor Allano, Irin and I had purchased at the colorful Super Cheap supermarket in Phuket.

“Aroi maak maak,” she said sincerely as she took her first swig of margarita, after having downed a mojito in record time. As ever, she was understanding and un-judgmental when I decided to go home long before the party ended.

Which made me feel all the more terrible when it dawned on me, almost immediately upon unpacking my things in the small palm-shaded bungalow that had once been the family’s Airbnb, that I couldn’t possibly stay there longer than a night. And not just because of the disrepair it had fallen into during the nearly two years foreigners had been banned from entering Thailand.

Allano had gotten a cat—three, actually. And I am extremely allergic to them.

The next morning, after Allano took me to tick sunrise over Phang Nga Bay at Samet Nangshe viewpoint off my bucket list, I moved to the over-the-top Erawan Hotel in Khok Kloi, the town in whose fresh market he buys produce for J’Nong’s restaurant.

All members of the family insisted they understood why I’d made the decision I did, but I felt ungrateful and guilty—and, most of all, sad—just the same.

I woke up Friday mostly thankful to have slept the night before. I’d returned from dinner to find one of the largest spiders I’ve ever seen beneath the foot of my bed; only after the hotel staff came to remove it did I see its cousin, which was actually atop my comforter.

Indeed, although the Similan Islands have been on my bucket list for years, I wasn’t especially excited to be going there as I hopped into the tourist van. It arrived right on schedule at 7:20 and which was empty, apart from myself, the driver and four Russian tourists.

Then, as the van started speeding northward through the rubber and oil palm forests of rural Phang Nga province toward Khao Lak National Park, it dawned on me. The sun this is, and I mean literally: The foreboding grey of 48 hours earlier seemed as far away as the pre-pandemic era.

Upon arriving at Khao Lak Pier myself, the four Russians and about 30 other tourists of various nationalities partook in a complimentary breakfast. Toward the end of it, a young-ish Thai man took his place at the front of the outdoor seating area.

Behind him, the waters just off the dtaa ruea were sparkling in the perfect light. This begat their stench, a mix of the petroleum swirling atop them and leftover fish carcasses from the nearby seafood market.

“Thank you for coming to Thailand,” he emphasized, after briefly introducing himself and outlining the tour program. I found this heartening, given that recently changed in government policy made it clear Thai officials don’t feel the same way. I quipped about one of them in particular; only Arty (whose name I initially thought was Aathit, or “sun”) reacted to it, which was fine enough.

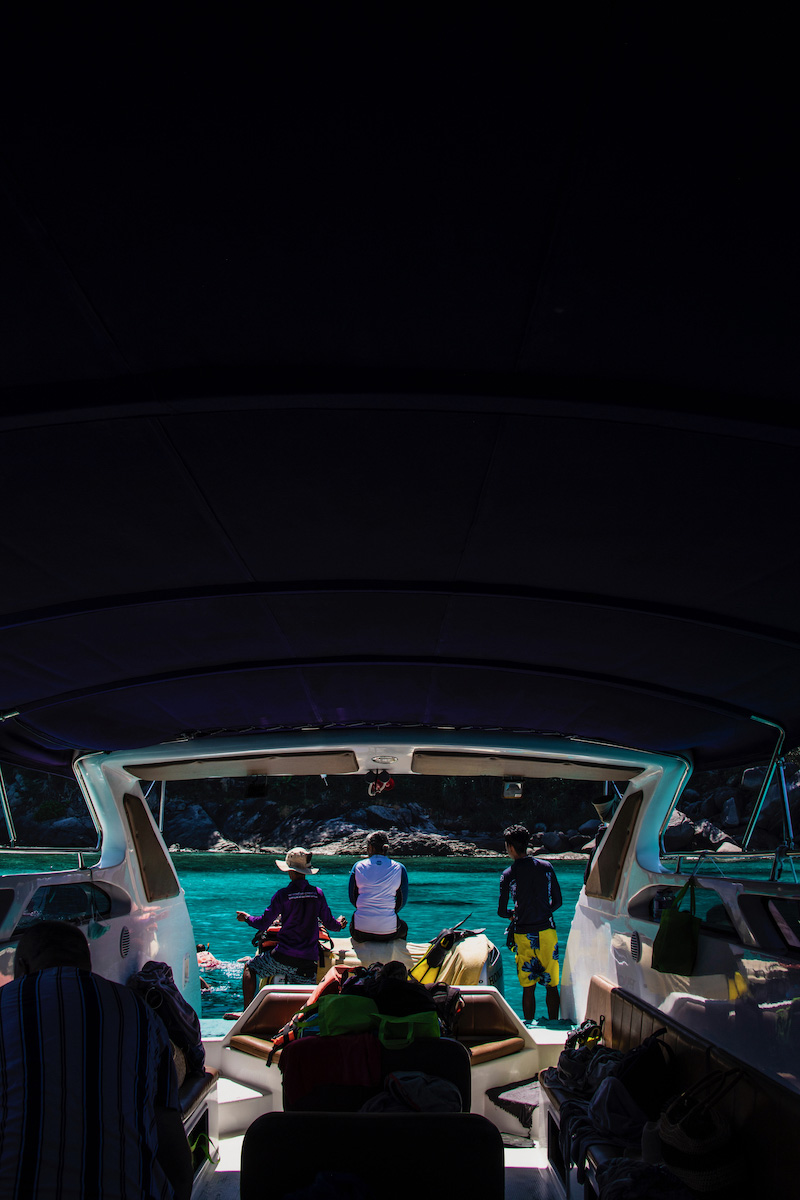

As Arty said it would, the speedboat journey to Koh Miang (island #4) took exactly one hour and 15 minutes. While I found myself annoyed that everyone besides myself and the Russians donned their masks for the entirety of the boat ride, this all melted away immediately upon arriving in the pristine bay.

In terms of beaches I’ve actually been to, the powdery sands and bottle-clear cyan water reminded me most of the islands of Myanmar’s Mergui archipelago. The large boulders at the eastern end of the beach, however, evoked the Seychelles (where I have not, as of January 2022, been).

And yet the sublime serenity of arriving there, not fully grasping the breadth of the beauty I’d be faced with, actually called to mind my time at Turkey’s Pamukkale travertine the October before last. (Yet, I realize it’s not a beach; it made me feel the same way as arriving in the Similan Islands did no less.)

Certainly, the beach is the sort of one I thought of when I insisted last year to a friend from Sardinia (which I found terribly overrated) that Thailand’s beaches were generally better than the ones of her home island.

After a photoshoot amid the aforementioned stones, I ran into Arty, who seemed surprised that I was traveling alone. But in a good way, which is the opposite of how most Asians react.

“I like to travel by myself too,” he admitted, seemingly as enthralled with the scenery as I was based on his expression. “Well, when I’m not working, which up until 2020 seemed like always.”

I learned that like me, Arty had also been in the tourism industry since 2009, first working for a large Phuket tour company running dive tours to islands like Koh Racha and Koh Haa, before coming to work at Wow Andaman, which allowed him to be closer to the village where he grows up and still lives.

He thanked me personally for all the time I’d spent in Thailand, but struck a more somber note privately than he’d done publicly.

“We might lose another high season thanks to the changing rules,” he sighed, somewhere between desperation and resignment. “Today’s boats are full, but we usually have five or six of them. Now we only have two.

“Do you think things will ever go back to normal?” He finished. “Like before?”

I nodded. “They will if the people in charge let them.”

In our brief, bittersweet moment of solidarity, I remembered an important truism: Experience erases anxiety; perspective defuses bitterness.

On the next two islands, Koh Similan itself (#8) and Koh Hin Pousar (#10), the focus largely moved underwater.

Arty, for his part, directed myself and several other fast-swimming snorkelers toward a variety of marine life. These included a rainbow parrot fish, a sea cucumber and a so-called “black Nemo,” which was both smaller than I expected and also indistinguishable, at least through my fogged goggles, from a normal clown fish.

And yet, in my desire both not to appear weak—there was a current in the bay—and also not to let Arty’s kind extracurricular guiding go unnoticed, a strange thing happened. I finally hit my snorkeling stride in a way I’d never been motivated to do since doing my “Discover Scuba Dive” (admittedly, my only one yet) at the Great Barrier Reef 10 years earlier.

Before leaving Koh Similan itself, we had lunch just behind its main beach. There, a monitor lizard like the kind that lurk in Bangkok’s Lumphini Park was slinking through the picnic tables like a dog begging for table scraps. We then hiked up to the Beacon Rock viewpoint, where Arty pointed out a few other factoids to me.

In spite of the beauty of the bay far below, its coral had apparently been badly damaged over the decades. “Indonesian fishermen used to come here,” he explained, “and used dynamite to scare the fish out to the reef.”

He also did his best to point out a small waterfall that apparently ran between two of the tightly-connected boulders just behind the main beach. My eyesight was definitely too poor to see them; I humored him and took his word for it.

Our brief tour of paradise—and certainly, the best islands I’ve yet seen in Thailand—drew to an end five hours (but seemingly five minutes) after it began. As I loaded my weather app to take a screenshot to send to my sister in freezing St. Louis, the label brought a smile to my face.

Indian Ocean, it read, without providing any other geographical context.

Saturday morning was supposed to be anti-climactic. When Allano arrived at the Erawan to fetch me, I assumed he would simply be driving me to Phuket for my interstitial three-day trip, and that I wouldn’t be seeing him again until I came back to Phang Nga the following week.

Instead, he dropped me off a J’Nong Recipe, where as per usual, J’Nong herself had prepared a delicious meal for me. Today’s included many of the same favorites I’d had one other days, with just one special request—Tom Kha Gai—on my behalf.

What was unusual was the company. A friend of J’Nong’s also named Nong, who was also a chef and also originally hailed from Phang Nga, but who was currently living in Guam. Alongside him were his daughter Am and wife (maybe ex—I didn’t ask), who ordinarily lived in Thailand’s Phattalung province.

“It’s my first trip home in three years,” he explained excitedly, as he shoved stewed pork hock and spicy fish stew into his mouth. “Zero dietary restrictions.”

On one hand, the experience of meeting J’Nong’s friends felt like an honor. These were people she’d known for decades; I was just a friend her son happened to meet a few years ago under somewhat unsavory circumstances.

Indeed, it seemed strange that Allano and Irin ate in the back with the staff while I dined with the man, whose presence made him seem more like a visiting foreign dignitary than an old pal.

Well, except for the glee with which he photographed literally every piece of food that came out—it almost reminded me of me if I’m honest.

“I’m a member of the Instagram generation,” he joked, the smile on his face as wide as sugary beaches of the Similan Islands.

As he was describing the tempura-fried greens on his plate—pak lin han, which are apparently found only on the beaches of Phang Nga province—he spoke with an enthusiasm that evoked someone finding a rare Pokemon.

When we arrived next at Home Cafe (stylized as the Chinese character 家), my excitement level ratcheted up as high as his. Owned by Allano’s family friend Pong, and adorned with antiques and photos from his Hokkien Chinese ancestors, the café evoked Penang more than Phang Nga, in the best possible way.

And this was even before Pong brought out delicious food and dessert, the centerpiece of which was a generations old recipe for Aiyu, a delicate gelatin made from fig pectin.

As we ate and chatted in the house (which in spite of its antique look had actually been built only a year earlier), photographs of at least five generations of Pong’s family stared down at us.

“These dishes all go back at least as far as her,” he pointed to the woman at the top, his great-great Grandmother. “So it’s a 170-year old menu.”

I couldn’t help but feel like the old woman was staring down at me, gauging my reaction. Although the photos were colorized and of a quality that made them appear drawn rather than printed, there was something visceral—something human—about them.

These people had already lived all the years I have ahead of me, died and turned to ash before I was even born.

Pong’s hospitality, it turned out, rivaled even J’Nong’s. After several savory dishes and three different presentations of aiyu (honey-lemon, watermelon and peach), he brought out another bowl of rice with pork balls and fried garlic.

The other Nong took a break from Instagramming and eating to ask me if I wanted some.

“Im laaw jing,” I finessed an answer in Thai, more certain than not that I’d gotten it wrong.

Nong confirmed this for me. “‘Im jing jing’ would be more natural. I understood the way you said it, but it sounded funny.”

Outside, the sun was almost directly overhead; the cool (for southern Thailand) morning air had risen to nearly 40ºC, to the extent that we could feel it waft inside. Although I wasn’t in a rush to reach Phuket, I did fear that if I waited much longer to go, my hotel there would think I’d flaked.

Back at J’Nong Recipe, waiting for Allano to get ready for our drive, I flipped through some of the photos I’d taken earlier in the day and also, through the several hundred I’d captured in Thailand before then, which were all in my computer. I had hit my creative stride again, for the first time since I departed Italy at the end of September.

When Allano finally arrived about an hour later, the initial perturbment I felt as a result of his delay melted away instantly. Joining us in the SUV would be Irin and J’Nong; it would be a real family road trip. If I’m honest, I’d felt guilty about the fact that I’d be getting chauffeured all the way to southern Phuket even when it would just be Allano doing it.

I was extremely grateful everyone else was coming along, but somehow felt undeserving of the send-off, particularly since I’d be coming back three days later. I offered to take a cab on the way back; I got no confirmation if that would be necessary or not.

Our conversation on the way down, to be sure, was nothing if not familial. It spanned topics ranging from the freshness of the bag of oranges we’d brought into the car with us, to why I’d chosen a small hotel away from the beaches Thai travelers usually prefer, to whether I’d even eaten stinky bean salad (I haven’t), to Allano laughing about the viciousness of certain negative Google Reviews I’d left for other businesses. They apparently sounded much more vicious (and, therefore, much funnier) in Thai than they had in English.

It was dark by the time we reached Kata Beach, and while I didn’t feel sad for the temporary goodbye (the semi-permanent one was still days away), I did feel the sort of un-repayable gratitude that makes former Catholics like myself feel guilty about to the point of genuflection.

“My Thai family,” I said in English, and then in (probably wrong) Thai, group hugging the three Sanguannams as the car sat running with its emergency flashers on.

When I set my phone down inside my bungalow, I had a text message from my American father. “Hope all is good for you in Thailand,” it humbly read. “Heading out to the trail. About 18ºF!”

Other FAQ About Visiting Phang Nga

What is the best time to visit Phang Nga Bay?

Like most of the rest of Thailand, Phang Nga province experiences its dry season between about November and March, give or take. “Shoulder” months like October and April can also be pleasant, but do keep in mind that October can still be wet, and April can be unbearably hot.

What is Phang Nga Bay known for?

Phang Nga Bay is known primarily for its karstic rock formations, which tower dramatically out of its crystalline seas. The most famous example of this is Koh Khao Phing Kan, aka James Bond Island, with the second-best vantage point being the Samet Nangshe viewpoint on the mainland.

How do you get to Phang Nga Bay?

Boat trips into Phang Nga Bay depart both from Phuket as well as from mainland Phang Nga province, usually from various ports in the vicinity of Samet Nangshe viewpoint. If you’re staying in Phuket, tour companies can usually pick you up at any beach; in Phang Nga, your best bet is to stay in Phang Nga city or Khok Kloi town.